How to become an architect in a company

Sooner or later, companies reach a point where architects are needed, but it can be difficult to hire them on the market, so they have to be trained in-house. Training takes place when someone within the company wants to move towards architecture or when promising people are found in the labor market, if, for example, a person falls slightly short of the required position.

Teaching architects is, in my opinion, a rather difficult task because architecture is poorly formalized and heavily dependent on the organization's context. Since I do not consider myself a specialist in training, this post will change from time to time as I make mistakes and find better approaches.

Who is an architect?

To understand what to learn, you need to understand who an architect is.

I must say that this is a rather non-trivial definition, as it strongly depends on the organization. Nevertheless, I will try to generalize it.

So, an architect is a role that solves business problems taking into account the current structure of the organization and its current technical components. Sounds like a description of any developer, right?

So what's the difference? Usually, the difference lies in two tasks.

The first task is operating at higher levels of abstraction. At the level of abstraction that affects two or more subsystems and their interactions. This often includes subsystems that are owned by more than one development team. Of course, there are cases where the team that implements everything is one. In this case, the architect takes on the role of the most experienced developer in the team who determines how to build the system.

The second task is to develop a vision of the system and an understanding of how it will evolve over the time frame that is important for development and support. In other words, the architect must understand what needs to be created when there is nothing at all.

And yes, there can be different types of architects, such as solution, enterprise, information, data, infrastructure, and so on. I'm trying to describe the general case and fair things for the average company architect, but if it's easier to assume a specific type of architect, let's assume a solution architect in this article.

What should be the starting point?

The first thing is a strong technical foundation. It should be a person who has effectively and qualitatively solved technical problems. After all, architecture errors can be costly. Quality should not be compromised for speed for such a person. At the same time, fundamental knowledge should be valued more than knowledge of specific technologies. That is, if a person knows data structures, networks, and databases well, it is more valuable for an architect position than good knowledge of Java. Of course, confident knowledge of a specific technology is a plus, but not a mandatory condition. I do not mean complete knowledge of specific technologies. Of course, a person who has been an engineer for a long time should understand the technology he has worked with for a long time. I mean that you may use Java, and the candidate understands dotnet. This does not mean that such a candidate is automatically unsuitable, especially if he has good fundamental knowledge.

The second thing is experience. Unfortunately, experience is important for the position. A person should understand how the composition of systems works and what consequences technical decisions can have. It is important that the experience is as practical and production-oriented as possible. That is, if a person has little experience in a production environment, it will be very difficult to grow an architect who will approach technical solutions responsibly. A person who has experienced the benefits of a production environment will approach solving technical problems with empathy for the team or teams that will implement it.

Learning plan

Next, I describe the main skills that, in my opinion, need to be developed in order to be able to work effectively as an architect and interact with teams.

Working with requirements

As I see it from experience, this is one of the most important skills for an architect. And yes, I'm talking about the architect, not the business analyst or product manager.

Why is this important?

Because architecture begins with meaningful requirements. I often hear from development teams that the requirements are not precise enough or not sufficiently specified. In the case of an architect, this is not an acceptable luxury. You need to develop the ability to work with sufficiently vague and fuzzy requirements at the very beginning.

What is important is the ability to translate from the language of business to functional and non-functional requirements. As I mentioned earlier, this article is not about business analysis, so we don't need a detailed specification of the requirements. At a minimum, most companies now work with agile methodologies, and creating a detailed specification is not an acceptable luxury because the time and effort required to create a detailed specification can seriously slow down fast-moving development teams.

Based on the input from the business, you need to be able to identify architecturally significant requirements. Architecturally significant requirements are those that affect either the number of subsystems or the number of connections at the chosen level of abstraction, or the quality attributes of the system. At the same time, you need to ask the right questions of the business and make the right conclusions from the answers. For example, asking a new business about the number of requests per second or the expected number of users is often meaningless. Of course, it is a great situation if the business can answer this question, but in most cases it is better to ask about how they plan to attract users, what the scale of marketing and advertising campaigns will be. Based on the answers, you can draw conclusions about the expected load, as well as requirements for scalability, throughput, and elasticity, which is more valuable than just a randomly selected number of users.

In terms of learning, you need to:

- Clarify business requirements and ask the right questions

- Identify architecturally significant functional requirements

- Identify architecturally significant non-functional requirements

- Understand what quality attributes are and how to extract them from input data and organizational specifics

- Analyze trade-offs, make decisions based on them, and communicate them effectively

Resources:

- "Software Architecture in Practice" - a book that describes quality attributes and strategies for achieving them. It's quite dry, but it helps structure approaches.

- "ISO 25010" - a standard for quality attributes that can be used as a catalog to ensure important aspects are not overlooked when defining requirements.

- "Fundamentals of Software Architecture" - a book that describes the basics of architecture. It contains examples of architectural tasks that can help understand how to define requirements from concise inputs.

Breadth of Technical Knowledge and Skills

I am extremely skeptical of the specialization of architects. To be more precise, there are certainly specific areas that require specialization, such as developing tools for a particular technology. For example, if we are developing an application performance monitoring (APM) system, we may want a .NET architect to develop .NET APM. But in most cases, broad specialization is more important than narrow knowledge. Especially, I don't believe in front-end architects in web development.

Why is that?

Because based on the definition of architecture above, architecture is a solution to business problems. And a business problem usually involves many parts of the system, which can only solve the problem by interacting together. Removing any element of the solution will leave the business problem unresolved. Therefore, to have the ability to solve the problem from start to finish, a broad perspective is needed.

How to develop it?

Work with different technologies. Solve tasks that go beyond one area. If the work is only on the frontend, start solving backend tasks or participate in infrastructure development. If the work is on the backend, start solving infrastructure tasks or frontend tasks. And so on...

It is also important to keep up with the latest trends and news in a wide range of areas. Subscribe to newsletters not only in your technologies, but also in adjacent ones. Despite what is happening in the current workplace, it is important to understand what is happening in the world, what trends exist, and what is no longer relevant and why something is no longer relevant. All of this will help in current tasks to assess how development at the current workplace differs from global trends, understand why this is happening, whether what is happening is a conscious and pragmatic choice, or whether it is a stop in development without clear reasons.

From a learning standpoint, you need to:

- Start actively looking at adjacent areas of responsibility to your main specialization

- Keep up with public materials related to various development areas

Resources:

It's hard to recommend any specific resources here, but at least you can keep an eye on the Technology Radar. And keep an eye on the top on platforms of your choice, such as InfoQ or DevZone.

Effective Technical Problem Solving

Although I ranked it third, this is a critical skill that is essential for any architect. Whether directly or indirectly, architects must solve technical problems. "Indirectly" refers to any activity that requires resolving technical issues but does not primarily lie with the architect, such as code reviews, mentoring other architects or teams, and so on.

What does solving a problem entail?

- Understand what needs to be resolved. This refers to the requirements described in the requirements section above. Extract the requirements from the business and add requirements based on the organizational aspects.

- Ability to break down the problem into clear and concise parts and make decisions accordingly.

- Based on all of the above, create a suitable artifact for the problem resolution, be it documentation or code.

- Present the solution to everyone involved in development and interested parties.

- Finally, control the implementation. Ensure that the goals set by the architecture have been achieved during implementation. It's also essential to accept feedback, especially if some parts of the architecture weren't adequately thought out, and make necessary corrections to the architectural artifact while learning from such experiences.

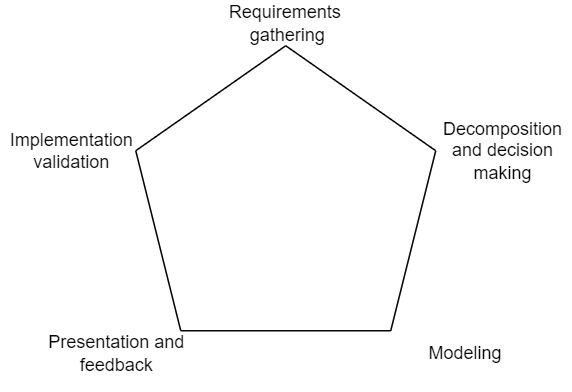

At the Software Architecture conference by O'Reilly, Eltjo Poort described this as a maturity model in the form of a pentagon. However, for problem-solving, I define the edges a little differently, as shown in the diagram below.

This pentagon can help assess your current skills and determine where you should aim to be.

Resources:

- Fundamentals of Software Architecture - This book describes the fundamentals of architecture and provides examples of architectural tasks, as well as descriptions of architectures that can be applied in different situations.

- Designing Data-Intensive Applications - This book provides a great description of different data models.

- Courses, books, and collections on system design. I don't have a specific resource link, but there are plenty of examples of how to do system design available online.

General Soft Skills

Here are a few additional soft skills that I consider essential for an architect. You could be technically proficient, but without these skills, it can be challenging to perform your duties.

Articulating Ideas and Presenting Work Effectively

Since architects must communicate with people in various roles within an organization, it's essential to convey your thoughts clearly and concisely. This means that during conversations, you need to understand who you're speaking with and tailor your arguments and language to suit the context of the person you're speaking with. For example, when communicating with a development team, you can use deeply technical terms. However, when discussing the same topic with a product manager, you may need to raise the level of abstraction and avoid deep technical terms. You need to explain the entire logical chain to the product manager, while the technical team can omit some links as they are deeply rooted in technology context.

Negotiation skills

Once again, the work of an architect is multifaceted. Unfortunately, situations such as conflicts or compromises are inevitable from time to time. Compromises often involve different roles and different people who may have different points of view. Even when you have a clear, well-formed opinion, you need to be able to convince all stakeholders with whom you need to negotiate. Another example of a situation where negotiation skills are essential is situations where decisions that lead to a significant shift or investment in development need to be conveyed.

There is an excellent book that helped me develop my negotiation skills - Everything is Negotiable. It's easy to read, and it describes various negotiation situations and how to come out on top.

Pragmatism

Everyone wants to try something new, do something risky, follow what's described in a popular article on a popular resource, or was talked about at a trendy conference. But unfortunately, we all know stories about what quickly became legacy, such as MeteorJS teaching us that hype is good, but when making a choice, it's worth considering other factors besides the technology's trendiness. Projects on MeteorJS are now legacy, which needs to be maintained. I'm not trying to say that MeteorJS is a bad technology; I'm more about approaching the choice pragmatically, evaluating risks and the current context. Sometimes, this can lead to a lack of understanding within the team or the demotivation of some people. Why do we need to use PostgreSQL if there are trendy NoSQL solutions?

Mistakes in architecture can be costly. You need to be able to find the line where you make risky decisions and where you choose a time-tested solution because it fits the task directly. Sometimes, of course, you can use risky technologies, but you need to understand that there are tasks where it is appropriate, and there are tasks where you need to stick to pragmatic solutions.

Conclusion

I hope this article will help engineers with organizing their learning, or for those of you who are choosing a promising candidate for an architect position. It's essential to remember that architecture mistakes can be costly, and learning to be an architect is a complex field. Therefore, we all need to approach learning with sufficient effort and thoroughness.